Dear diary - the temperature has changed.

Everything feels like it’s changed really and I’m not 100% sure how to feel about it.

I was speaking to my manager last week and he asked me about why the temperature seemed to have changed and I think it’s a really good way of speaking about this moment.

Last year I wrote a post with some general predictions about the effects of generative AI on computer programming, and in the time since we’ve watched the gradual improvement of models, open-source models start to “get good” and more importantly an entire category of tooling evolution that powers what is currently the state of the art in model assisted programming. And oh boy does it make me feel a lot of things about programming.

I’ll start with the clickbait:

I think programming might be over?

And I’m kinda sad and angry and excited about it in equal measure.

There’s been plenty of headlines like this over the last couple of years since Copilot launched, and the tools that followed. I talk to a lot my peers about this almost daily - about the hype cycle, and what it means for people who write code, and what it means for the industry, and the world. And I’ll be honest - for the past couple of years the sense has been “yes, these are useful tools, we’re not quite sure if the juice is worth the squeeze, but the tools are clearly moment-to-moment useful and they sometimes are so incredibly dumb”.

Nobody outside of the hyperbolic vendor headlines was really thinking “hey, this is an existential threat actually”, but I’m starting to think that maybe it is, and that we’ve marched down the path from the piece I wrote last year much quicker than even I expected us to.

You know the thing that the marketing said last year, about Copilot being able to automate most of your programming job, and then you tried it, and it didn’t really work and you just got on with your day?

The temperature changed. It works now. The slow, onwards march of technology took hold, and it works now, and it wasn’t really model innovation that did it, it was boring old programming, and model assisted systems.

In late 2025, just as everyone was signing off for Christmas, the latest generation of frontier models hit the market (Anthropic’s category leading Opus models, Google’s Codex model’s) and in conjunction with a significant uplift in the tooling around them, the promise of effectively autonomous developers is now reality.

Anthropics Claude Code, OpenCode and GitHubCLI, have effectively commoditised the market in software creation almost overnight. You can now ask your computer to build a thing (at least in existing software) and basically leave it to iterate until it’s done. It’s not particularly expensive, and the changes are generally at least of the same average quality as a blended skill Enterprise development team.

It kinda feels like it happened overnight - that moment when it all suddenly got good. But it’s here, and it’s real, and if you tried these tools last year and thought “huh, neat trick, but not good enough” you owe it to yourself to just give opencode a go. It’s night and day. Category changing workflow stuff.

So when we’ve rolled around to February 2026 and I start seeing hyperbolic sounding pieces by the FT, or quotes from Microsoft’s AI head saying words to the effect of “all blue collar jobs will be gone in 24 months”, I think I’ve gone from being an AI moderate who thinks “hey, these are useful tools but the human in the middle is central” to maybe thinking that there’s a non-trivial chance that that’s actually a reality now because I have seen it with my own eyes.

If you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes

So I think I’m about 6 weeks late to the party here - I was busy, I took mid-December to mid-January off work. I didn’t really touch a computer for anything other than playing games, and I tried to keep my head away from “the discourse”. One of the most troubling things about considering AI is the number of agendas, snake oil salesmen, and people that get filled with incandescent rage at the mention of AI that are already in the room. It’s exhausting trying to just work out what the fuck is going on in the cacophony of it all. But while I was away, everything changed and the tools got good.

So when I got back to my desk and decided to really take these tools to task in anger in their latest incarnations, with the latest models, I was astonished how far the goalposts have moved. It’s just so obvious to when you listen to the kinds of voxpops coming from the organisations now. They’ve stopped talking about AGI, because I think everyone has collectively realised that they don’t need to chase that unattainable beast to be category defining anymore - in fact - the models don’t even really need to be any better than they are now.

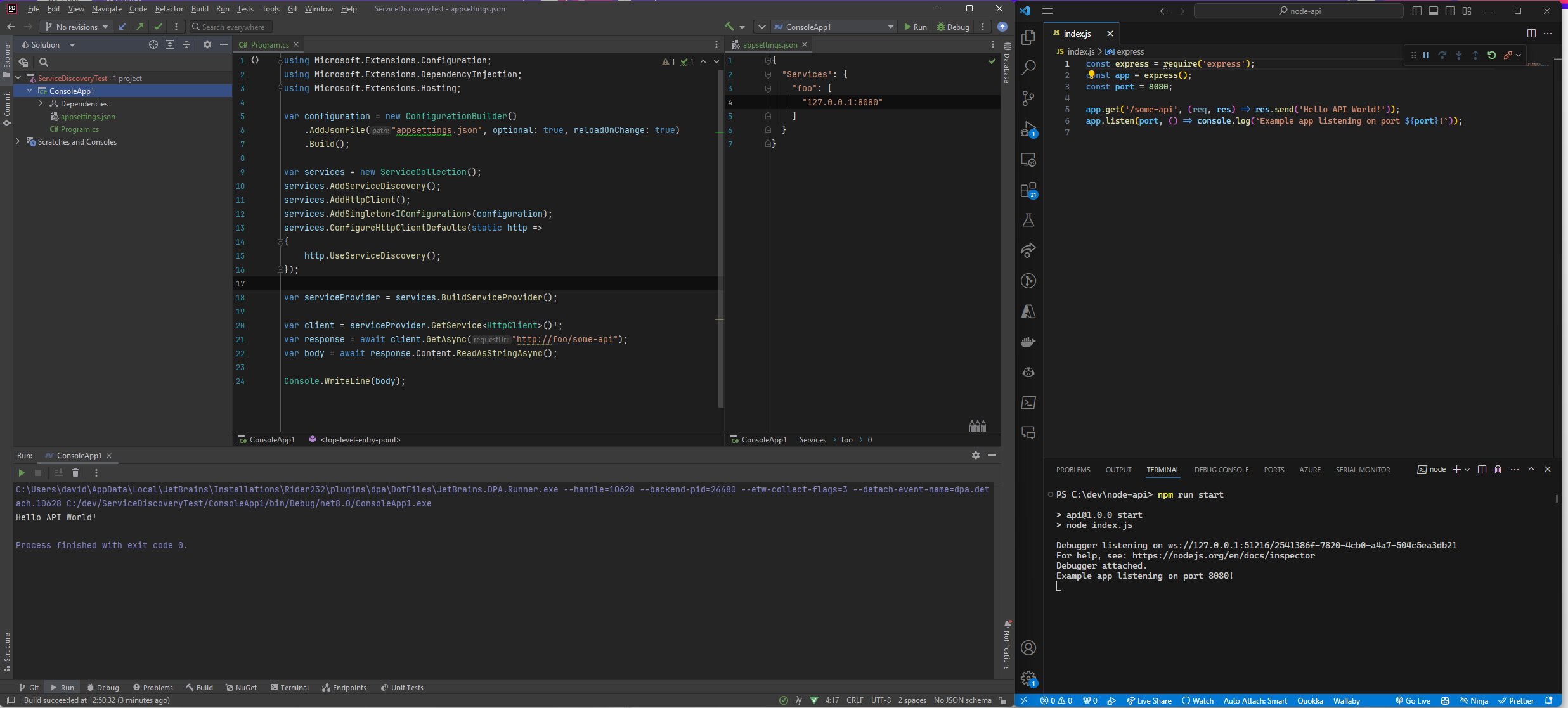

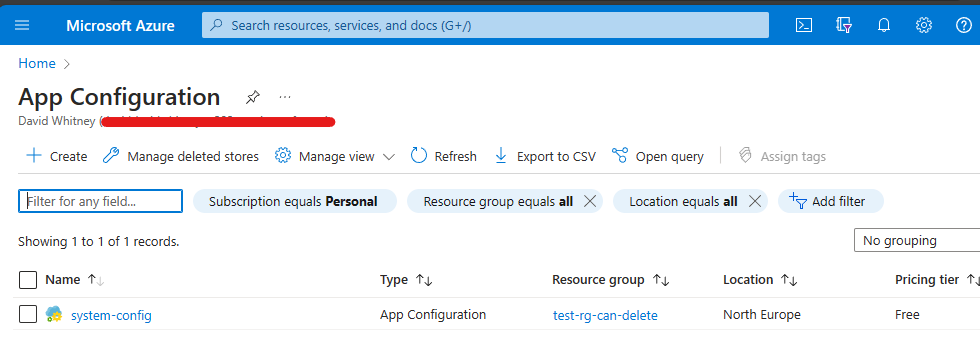

This new category of tools appears to outperform good-to-average engineering teams at almost all rote tasks, and excels at deep algorithmic, bounded, or deeply technical work. It didn’t require any real trickery, the current workflow just requires a bunch of iteration and increasing context management between the users computer and it’s ancillary tools via MCP, and a capable model. I’ve spent the last month immersed in real-world experimentation solving problems with these tools that would have taken me weeks to months to solve by hand, in minutes-to-hours-to-days. It’s real. I’ve seen it. I’ve shipped it to production.

Here’s a real world example - I was shipped an extract of some mainframe data for a project. No schema, no specs, just an encrypted and compressed backup and a Win32 data viewer tool designed for computers with a minimum spec requirements of a Pentium 233mhz computer. I set an opencode agent using Anthropic’s Opus 4.6 model the task of working out:

- What the format of the data was

- How to decrypt and decode it

- To build a C# program to stream decoded data

- To render the contained files to PDFs

In absence of any schemas, file format names, or information of any real sort, I handed it a single PDF file exported from the tool that was supplied by way of comparison.

Within the first twenty minutes or so, it had run a bunch of heuristics to detect that the file was compressed by the presence of repeating block patterns, and as a result had a lead on the compression algorithm.

I suggested it investigate the Win32 tool.

It spent about 30 minutes writing python scripts over a disassembler to decompile the executable, annotate the assembly code to isolate where compression and encryption occurred and identified not only which compression scheme, but via extracting strings from the executable identified the 1990s era libraries that were used to encrypt and compress the data in the first place, allowing it to instrument, extract hard-coded keys, and unpack the file.

Over the following two days of occasional prompting, using visual diffs with the one sample file, it constructed it’s own renderer to build up output files that interpreted ancillary data shipped with the tool and produce compatible rasterised files, snapshotting diffs as it went.

I’m pretty convinced that if I’d handed this problem to any engineering team I know, they’d still be sifting through bytes trying to work out what kind of file they were looking at. I know, because I’ve done this kind of work by hand before - it’s all possible, thankless, detailed work that takes a huge amount of time, not a couple of hours while I was doing my emails.

So I think programming in the traditional sense might be kind of over?

Not a good enough example?

While it was doing that, I had a couple of other agents finish off a few languishing side projects that I’ve been working on for fun. I’m much happier with the code in these projects than I was expecting because the model can trivially mimic my own style based on the context of the rest of the program. It followed my design without me even asking it to.

Still not good enough?

At the same time as both of those things were happening, I was also running another session to build an interactive architectural map of the systems I oversee, using metadata and traditional static analysis to get there. I’ve wanted to do this for years but never had the time. It was finished by the afternoon.

I’ve never been more productive.

I’ve never been more exhausted.

I’ve never been more addicted to building now that it feels like all the constraints are gone.

So I open LinkedIn and see another rote headline written by someone that hasn’t bothered to even try anything like this, about how the AI bubble is going to burst, and it’s going to all melt down, and this will all never work and I just… don’t believe. This is category changing stuff. It’s here now. It works.

And you know what, even if the back fell out of all these organisations, the union of tools like opencode, Llama.cpp, LM Studio and Alibabas open weights models mean that the genie is out of the bottle and it’s never going away. You can run this stuff on a £2,000 MacBook locally at about 90% of the quality of the frontier models. Maybe the big vendors won’t survive but what we have is already category changing enough.

The software doesn’t even have to work perfectly, or be one-shotted for there to be a drastically reduced need for programmers to fix up what’s left. Most software is buggy and messy, it’s unlikely to be worse. The vast majority of software is a remix of a concept or a well worn idea that it probably doesn’t even need to be original to be good enough - most software isn’t original works.

This is a heartbreaking thought for me

I’m simultaneously having the time of my life building and am sat at my computer with the dread of looking at the end-times. Writing a hubristic AI post would be all the rage if I had an AI to sell you, or if this was good for me in any way, but it probably isn’t?

I’ve been writing code since I was 11. I can comfortably say that it’s a foundational pillar in my identity. I am a programmer. I am an artist. I use code to effect change in the world. I think in terms of systems. This is literally who I am.

I’m not being hyperbolic - you can go to YouTube and find hours of talks, podcasts and writing I’ve done about finding myself through creating things with software. I wrote a talk called “Decades in the Machines” about finding meaning and purpose in the work. I wrote a talk about “Intentional Code” about treating code as literature. I’m travelling the world this year with a talk called “Meditations on Code as Art” about seeing the humanity in code written by people which captures the political context it was written in.

I love programming.

And I think programming might be over and I don’t know what to do with those feelings.

There are plenty of other people who are reaching the same kinds of conclusions that I am, and over the last few weeks I’ve seen a bunch of “oh code was never the point, it was all about how we could make things or add value to businesses”.

I love making beautiful things with computers and the mechanical pleasure of doing it, so I think this shift in the commercial dynamics of software might well be the end of something I want to be doing for the rest of my life.

I’m also kind of, tired? I’m addicted to the feedback loop, but working as a conductor in the middle of a flurry of agents is a different kind of mentally taxing. When you first start programming, everything feels bewildering and unknowable, every rock is an infinite black hole of complexity as you lift in, it’s disorientating.

This last month deep in with the agents I feel like I’m a baby dev again - because the pace at which the teams of agents swirl around me producing new code outpaces my capacity for comprehension. I literally cannot keep up. I can’t understand the work at the pace it’s being created. It’s breakneck, and I feel like a child again trying to fit it in my head.

I’m pretty sure that pace hampers my ability to make good design decisions and find the form in the thing as I’d like it. But in the war of objective, not method, pace wins. When I first drank the agile kool-aid in 2005 I absolutely believed that pace of iteration was the thing that made great software, and I absolutely believe to this day that the best software designs are the ones that you can change the easiest. But man it hurts.

And what if we’re now in a place where how well the software is designed has literally no impact on how easy it is to change or not? What if it doesn’t matter - this thing I care about - this thing I spent so long obsessively trying to be good at. What if it just doesn’t matter at all?

I feel like a painter at the dawn of the camera. Not yet irrelevant, but my interests are probably now a niche, even if the rest of the world hasn’t quite caught up to that thought yet. I will still do this as long as I live, but what I do to live is probably going to have to change.

If I can’t paint for my supper, perhaps I can still compose a great photo.

An existential threat to all business

I think businesses should probably feel more threatened by this than they are.

If the bubble doesn’t burst - and I don’t think it will - and the frontier models stay about 10-15% ahead of the current open-source and open-weight models, this will represent the largest shift of knowledge work and the associated profits towards the hyper-scalers we’ve ever seen. We might be looking down the barrel of the gun of outsourcing all programming to a small handful of companies - and that sucks for everybody.

And really all of this basically calls into question if software itself really has any intrinsic value.

You might have noticed the existential dread all the venture capitalist firms are currently experiencing, because the thing that’s worked for them predictably since about 2005 - building SaaS products and capturing market share - is basically a broken model if anyone can generate low stakes business software to solve the mostly trivia automation problems their solutions solve.

When code is almost free to write, it has no value at all. And subsequently, all code written with a tool that literally everyone has access to is intrinsically worth nothing. It challenges traditional software economics where the conventional wisdom is you should buy anything that’s outside of your core expertise, and build what is, because building entire categories of traditional enterprise software might actually be cheaper to own and maintain than licensing it.

Conversely, operating software reliably, being a good custodian of the data that it trades in, and cultivating organisational knowledge that can be “sold” via integration to provide context or operations for the models that are eating all the low-stakes software is probably priceless in this emergent economy.

We’re perhaps seeing the death of “algorithmic programming” in all but niche and specialist cases - because we finally found a general purpose algorithm for data processing and it’s simply a “good enough” statistical model of the world. I’d be remiss not to highlight that “the map is not the territory” - a statistical model of the world is just a model, and will not conjure accurately all the time, but the reason it works so well in software is that software is a constrained, well documented problem space, with almost infinite training material.

While trying to solve for general purpose data processing we accidentally solved programming by mistake.

This leads me to think that the future of traditionally slow moving enterprise software is to be the fastest to adopt new practices, while keeping data sovereignty, correctness, and high availability at it’s core - some very traditional programming disciplines.

It’s quite likely that the future users of software, APIs and data that you produce is likely to be agent driven integrations, so when that’s the case, whoever is fastest and cheapest will win the business. Your software is effectively operating in a “price comparison site” style ecosystem, where the best ranked, highest available and most compatible API or skill wins the business.

With some irony, all categories of products that are about web discovery (like price comparison websites) are probably dead - there’s no purpose to algorithmic curation at the behest of a third party when your own agent can do that job for you trivially from available public data sources.

A year ago I was hopeful that this shift in the landscape would see teams not having to expand by working harder (exponentially working with more people) but instead by working smarter (better tool use by existing teams) - I think as I watch the kind of productivity increases that talented individual contributors can manage with these accelerants the more I think we’ll be doing “more with less”.

Less people, less overhead, less money - but it’s important to remember that the code was only ever part of operating a successful technology business. Keeping systems online, on-call rotas, support, escalation, outage support, trouble shooting - that stuff all requires people regardless of how good and self-healing your tools are.

Code output was only ever part of the problem.

For myself I worry that the shift in focus might result in the job of a software professional being more… boring? Us generally doing the less interesting work and coordinating tools, but I think there’s also a great opportunity for small teams to have much wider impact in organisations if they change the way they interact with software, I’ll come back to this idea later.

I think business software will be able to adapt to survive this due to the accountability wrapper that business support provides. Much of the value in business software is the liability shift between the consumer of the software and the provider. If they make a mistake, it’s their fault, regardless if it’s your outcomes. Consumer software on the other hand?

I think it’s probably going to be a bloodbath.

My not-so-outlandish prediction is within 12 months, Google will make a call on putting “app generation” into Android. The Android store is notoriously not quite the cash cow that Apples high value alternative is, with the quality of models available today, every single trivial app you might want “hey can I track my shopping list”, “hey track my workout”, well, why not let consumers generate their own apps, with their own features. It’s low stakes, they don’t even have to be reliable, and they can probably put ads in them.

Once that happens, whoever is first to get there breaks the back of any non-significant consumer software. There will always be a niche. There will always be apps. But the days of launch a small little app that does some neat integrations and makes some money to start up a business with are probably gone. Your agent will do it for you. Hell, it might just use it’s own memory to perform the task and keep a log without you needing any new software at all.

Where does that leave enterprise

I think there’s a truism - people often think of software as an asset when the real value of software comes with the extreme cost of maintenance.

Software costs more to maintain than it does to author - this has always been true - and having more software is not better than having less software. Much of the bloat in the enterprise IT stack comes from trying to solve for second order human factors - we subdivide systems, to fit more people around them, to relieve the maintenance burden, and parallelise the work. Then the larger the systems get, the harder the integration becomes and actually the initial burst of parallel productivity doesn’t really hold.

The biggest opportunity in Enterprise, is to be able to reason about these large, distributed, maintainer hungry systems as a cohesive whole powered by tools that let smaller groups or single individuals reason about vast systems. I think if one of the side effects of this is we have denser, more feature rich software that doesn’t quite require unnatural subdivisions to allow humans to reckon with it then perhaps that’s actually a good software outcome.

The most nimble organisations are going to work out how to use these next generation model assisted development techniques to build faster, surrounded with human guard rails and speed limits.

The human cost

My profession is about 55 years old and change in it’s current form, and this is the first time I’ve thought “wow, maybe the way we do this is going to be really different soon”. But I’m worried. I’m worried about the extractavist nature of the technology. I don’t know where the next generation of software experts are going to come from that can better guide these tools when they inevitably make mistakes. I don’t know how, or even if, the programmers of the future are going to have enough time under the desk, to do enough repetitions, to learn what good taste in software development looks like.

The thing that’s be noticable to me over the last two years during the nascent phases of modal assisted development is that the people that get good results from these tools already understood the “lingua franca” of software. If you know how to form language to reason about software, it stands to reason that the outputs you get from a human-language interface (which to be clear, is less precise, but more expressive, than a programming language) are going to be better than someone that doesn’t understand the “meta-language” around the profession.

I think this shift away from low level software competence will have to be compensated by a renewed focus on the large scale design of systems - because without correct instruction, or conducting, or producing the systems generated by these models will atrophy in relatively low quality.

It seems to me that what “counts” as low quality will probably change over time, shifting from “code that can be comprehended by humans” to “code that fits in increasingly small context windows, or can be subdivided to do so” as that will enable a more rapid tool driven iteration. I’m not really sure I like this, but it seems like an inevitable second order effect - it doesn’t really matter what the code looks like if vanishingly few people will ever read it. If you don’t like it, you just throw it away. It’s the microservices dream writ literally large.

Regardless, I think it’s going to be hard shift for people to deal with the deluge of software change. Programmers are going to struggle if my own experience of extreme context switching is anything go to by.

I hope organisations still understand the value of experts in programming, because those that invest and grow great engineers are going to be the organisations that operate software the best, and optimise it the best, and can correct it when it strays from the path. Even if “code might be over” I’m not sure programmers are just yet.

While so much of what we do in software is remixing existing concepts, innovation isn’t going to come from an existing corpus of information, but business innovation might. You’ll still need those experts if you want to do something actually unique.

Is This The End of Programming Languages?

One of the weirder (and personally heartbreaking) second order effects of a shift towards machine generated code is probably that programming language innovation will dry up over time.

Don’t get me wrong, people will still make new programming languages, but I’m not convinced anything will ever reach mainstream adoption when the criteria for mainstream adoption becomes “can the model write effective code in this”. We’re probably generationally stuck with the languages we already have, and incremental and backwards compatible improvements on those languages.

The models work best with JavaScript, Go, Python, C#, Java - mostly as a direct side effect of the amount of training data available at the point of training. I’ll be surprised if other languages ever manage to cross the chasm, because there just won’t be enough data to encourage widespread adoption.

This really means that the only real chance for a new programming language to “make it” is for it to be attached to a notable, important, human first project - everything else will probably be damned to enthusiast niches.

Maybe that’s a good thing - it’s felt for awhile like we’re at this wonderful point of programming language conversion where everything is basically good enough now, and everything works, so maybe we did it, we solved programming in it’s current form. There is no next generation language, there is no replacement, just steady evolution. Nothing will kill React.

How to stay ahead

It feels like the software teams of the next 5 years aren’t going to be doing the same things as the software teams of the last twenty, and this is probably an inflection point for re-invention.

As strong individual contributors learn to reason about distributed systems as a whole, I suspect the days of surrounding components with teams to “look after them” is going to be a thing of the past. We’ll need enough people to be on-call and reason about a system but we’ll finally be able to pull apart the biggest resource sink in modern development - cross team coordination, planning and orchestration.

I suspect we’ll see small teams of very technical people with business context doing wide-ranging change across large systems, reasoning about the systems in a tool assisted manner. The tools will help engineers understand the context as they direct and orchestrate changes that range from front-end to back-end.

These engineers will need to have taste, and they’ll probably be involved in early hand writing of some categories of code to establish patterns for the machines to follow in the first instance, but likely will accelerate to the point where traditional workflows of pull-requests and reviews don’t make sense when faced with the pace change can be made.

This will logically lead to more “continuous delivery” and “continuous testing” style systems that get piloted and automatically promoted and rolled back, rather than reviewed. This will scare a lot of organisations that already suffer with anxiety associated with continuous change, but the pace that model assisted development enables means that if organisations don’t get on-board with this approach, then their competitors will.

Good, supportable, scalable software still matters - because organisations will be judged by how well they perform when interfacing with automations, that instead of being a side-line for a business, will be the default way many people operate with their products.

What are the bets

- Any platform that doesn’t have cohesive predictable APIs will die

- Adopt Agent-to-Agent Protocol for interop (A2A)

- Adopt Payments Protocol (AP2)

- Invest in making web-content more agent friendly (serving Markdown as alternative content types)

- Equip small teams with frontier model tooling and the entire source code of an organisation to reason about as one cohesive unit - insist on permissive support teams shipping code changes at pace during the transitionary period

- Invest heavily in automated testing - even if it’s agent generated, because it’ll probably be the only testing that exists

- There will likely be a new role - the “full stack engineer” of this next leap. Maybe it’s “Software Producer”, maybe it’s “Product Engineer”, maybe it’s “Software Designer” - but it’ll likely be a job where the expectations are much more broad than they previously were.

I expect I’ll still be programming for the rest of my life, but I’m not sure what the industry around me will look like as I do it.